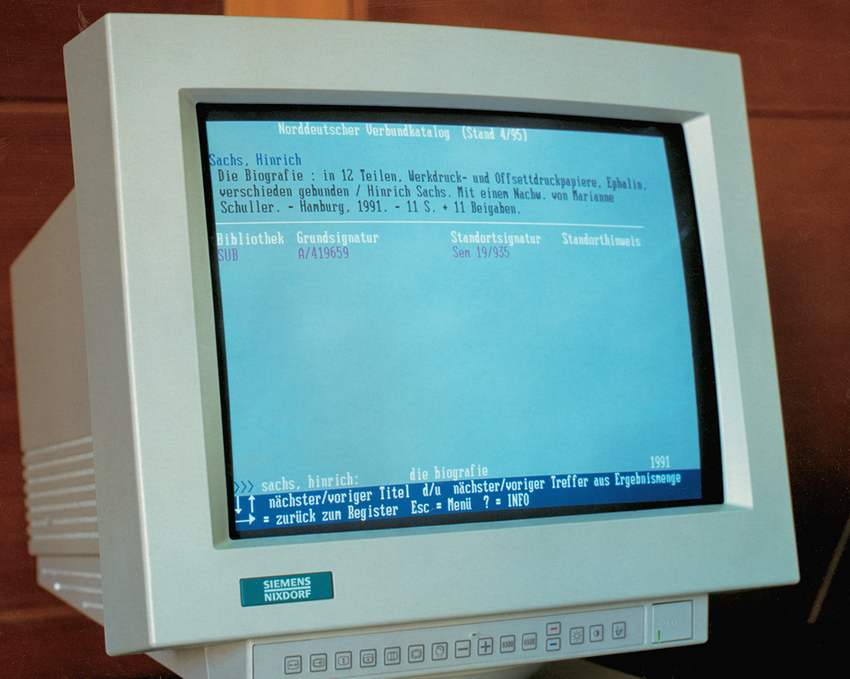

Die Biografie, 1991

A set of 12 volumes – 11 of them blank, the twelfth acting as a

kind of index merely constituted by titles –, various papers, various dimensions, covers in green heavy duty paper, blind blocking, letterpress printing, in an edition of six. With an afterword by the writer and literary scholar Marianne Schuller. Die Biografie

[The Biography], filed under several catalogue entries, is publicly accessible at the library of Hamburg University, DE, as well as in the collection of artist’s books at the Swiss National Library, Bern, CH. Other copies are held in private collections.

Views from the Hamburg University Library reading room, the digital inventory catalogue in the 1990s, a private collector’s home, as well as from the group exhibition The Liberated Page, Geneva, CH, 2014

Marianne Schuller

Afterword

It’s one of my favorites and makes me laugh. But then it is a joke. Let me write it down: In a Moscow gallery, a painting is on display showing Nadezhda Krupskaya(1) in bed with a young member of the Komsomol(2). The title of the painting is “Lenin in Warsaw”. Astonished, a visitor to the show asks: “But where’s Lenin?”

A guide quietly responds: “Lenin is in Warsaw…”

The title is what makes the joke. Why is this so? Evidently because it explains the picture’s content. Something like: when the forbidding father figure is away, things get going. From this perspective, the title stands in a metalinguistic relationship to the picture: the title knows what the picture is saying. Yet is that really all? Clearly: the title is outside the picture. But: it is also inside the picture. Then again: it is what is missing in the picture. The picture is what it is only because it shows Lenin is missing. The title reveals what the picture shows: an absence. Revealing this absence as the “essential” feature of the picture, showing that the picture is only what has been omitted from it, that is what makes the title funny.

But how is it with books? Isn’t it the opposite with them? The title does not reveal an absence but promises fulfillment. The title is like a recipe, it is what makes the reading of a book a feast. An announcement flatters across the front of the book: it does not say what is coming, but that something will. Only now does the book become an arrival: the advent of meaning, the revelation of truth.

Just as the title is the promise of a future, the afterword is the seal beneath the past. Framed between the future and the past appears the present: the time of the book, of reading, a lively time. In a presence produced in this fashion, the title becomes, in retrospect, superfluous: for it fulfills itself. Whereas the afterword gives fulfillment a voice again. It speaks of the meaning of the meaning.

From this perspective, life itself is a kind of book. Or rather, books! A library. Tell me your titles and I’ll tell you who you are. From this perspective, the trisection of title/announcement, reading/fulfillment and afterword, which distills the meaning from the meaning, repeats itself with each title. From this perspective, a stroll through my library – where title after title is lined up without a gap – can become a grand tour of my life. Unquestionably: here I am there.

Though it is by no means unquestionable that it may be otherwise. When we ask ourselves whose subjects we are, we are certainly (also) those of books. Some have happened by having an impact and leaving a scar. A trauma of consequence. It’s about books of enjoyment or rather the enjoyment of books. Why is this so? And why this specific book and that one? An answer is nothing but the bad fortune of a question.

For what happens when the language of books takes place? Certainly not the presence, that being there that is always the production of a frame: of the title and afterword, for instance. Perhaps the book even starts there where presence ends: in memory, which inscribes itself from the traces of traces of writing. So perhaps the book starts there where its phantasmatic presence defaults: deletes itself. Perhaps the book touches me when it speaks of its absence. And I, the book. The sublime is not

bound to objects.

But what becomes of the title? It is no longer the announcement of a future parousia of meaning and content but a remnant. A sort of slag that will be left over. A remainder, a surviving element. A beloved object that becomes bound to me and to which I am bound. My whole life long.

And it may come to pass that this absence, which the book invisibly depicts, lets us see something. That is, in our seeing nothing but the always-already deceivingly visible titles on title pages. We don’t see anything? Yes, of course, we do. We see and leaf through the empty pages of the book as it stands there bound. To the title, that bit of slag, strands attach themselves and we start reading the emptiness. Does it trace? Does it write?

In the joke, the title revealed that the painting is there only if something is omitted. The library on display lets us see what has always already disappeared in the visibility of the book. It lets us see in the visible the disappearing or the invisible that the book depicts. The title is a remnant. A mark, a label, around which our life revolves. And the afterword? It is long over and just calls out after it.

(1) Lenin’s wife

(2) Former youth organisation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Translation into English by Catherine Kerkhoff-Saxon