A Line of Development, 2019

‘The reason I stopped making art is much like the reason I started: you meet other people, you change. At some point I realised that art is no longer the best tool with which to position my values in society.’ (1)

In autumn 2004 an interview was first published in the Belgian art magazine De Witte Raaf entitled ‘Speelruimte vor beslissingen’ or ‘Scope for Decisions’, an interview Anna Winteler had taken part in with me some months previously. My interest then was to find out more about her decision to end her artistic practice. It was the first time for many years that Anna Winteler’s voice had been heard in an art context. And it was the voice of a contemporary who was broadly interested in culture, now a physiotherapist by profession, and someone who had also been witness to a particular period in the Basel art scene. Not an artist’s voice. We had remained in contact; we like to talk about literature and recently, for example,

we were discussing the question of what might be understood as cultural translation at which she drew my attention to Swetlana Geier’s method of working and how it can be observed in the documentary film Die Frau mit den fünf Elefanten. Another 15 years have passed since that conversation about the end of her artistic career till now, when deserved attention is being bestowed on her works in a survey exhibition. Yet our distance from the time in which these works were made and to their direct effect is not a disadvantage, for it allows us to inspect some things more closely than is possible contemporaneously.

What is significant – and the detailed survey of works confirms this elegantly – is that Anna Winteler’s body of works illustrate how visual art in the 20th century developed into what has, since the mid 1960s until today, been recognised as contemporary: contemporary art (2) with a drive to extremism and expansionism. Those tendencies all seem now to coexist peacefully.

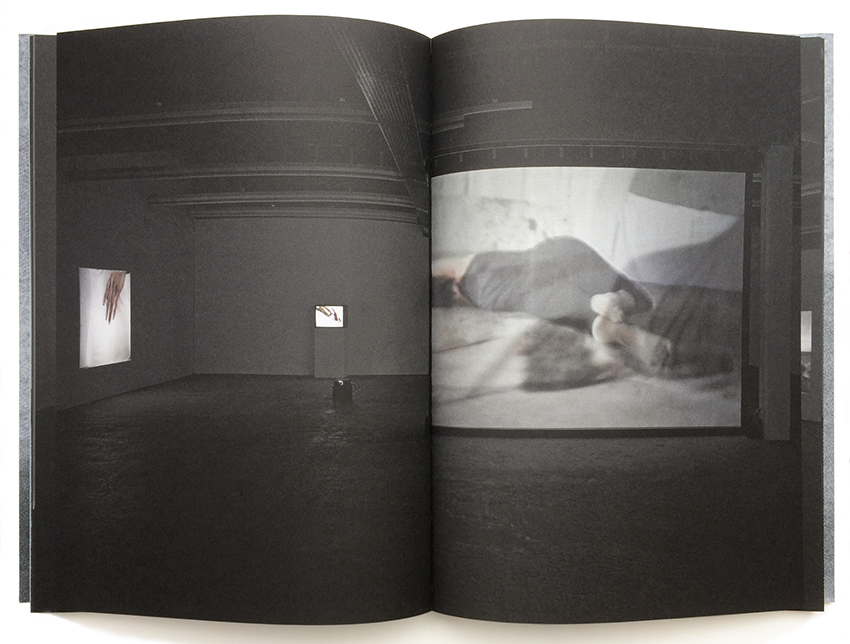

The by that time very broad field of contemporary art was clearly illustrated in Jeff Wall’s lecture and text Depiction, Object, Event. He concretely analyses how the avant-garde generation of the 1950s successfully ‘discovered the potential of the second appearance of the movement arts, the movement arts recontextualized within contemporary art as if they were Readymades. […] In making its ‘second appearance’, or gaining a second identity, the art form in question transcends itself and becomes more significant than it would be if it remained theatre or cinema or dance.’ (3) Performance and video art emerge, and by the 1980s at the very latest they are also part of the canon. And that was just the first wave of the expansion. The term Wall coins, ‘second appearance’, makes it self-evident how the performative and acoustic, not to mention the range of discourse-based praxes and methods of communication, can find a place within the framework of contemporary art. What makes Winteler’s now finished artistic work unusual for us as contemporaries of 2019 is the peculiar void marked by her decision to turn her back to art.

The provocation of this void lies in the fact that when she re-oriented herself in the year 1991 she abandoned dance, or more precisely in working with the body, in its ‘second appearance’ as art, as a productive method. Beyond all personal reasons, the conclusion of this work, which is as sensitive as it is reflective, posits in fact a question about the state of the conditions of art in the early 1990s. Perhaps performance had inherently reached a point of redundant form, and had to change. Which it did in multiple forms in the years that followed, in particular as bodily presence was exchanged for employed, delegated bodies. Winteler’s lucid use of the term ‘tool’ in this context confirms this reading. Let us repeat the question: what are the current conditions of art? Which forms of vital, poetic, critical image-making and which forms of subjectivity find an audience in the contemporary art system? It is the task of each new generation to reconsider what is possible amid a diversity of interests.

The retrospective project Anna Winteler Body Works is thus subject to particular demands. This book, accompanying the exhibition format, serves all readers as well as art-historical discourse – though in this case also the person of Anna Winteler who is both professional physiotherapist and a public person – as the place where the biography is fixed. Information regarding the origins and the life of any given artist are standard in a framing introduction and reflection upon works. Write down the name, and then usually the gender, of the person being considered and open the door: firstly to popular and mythologizing generalisations about this person – rejection, success, drama, eccentricities, etc. – and secondly, to substantiation of the sociological parameters of an artist’s role in the art world. (4) These standards then become normative in forms of paratext like that of the biography. The cliché, or the norm, of an artistic career remains to this day closely linked to the work produced, with its end in particular. (5) The anticipated entry following the late work is the date of death. Or, alternatively,

how an artist had an unexpected accident.

The independently defined end of an artistic practice is not, however, envisaged, certainly not as a life choice made with conviction. In 1968 Charlotte Posenenske decided to work as a sociologist; Laurie Parson chose an engagement with social work in 1994. In our 2004 conversation the physiotherapist formulated it a second time, very precisely: “I can envisage that the relationship between an artist and their creative practice is no longer understood as an existential calling.” Winteler after Winteler helps us to positively reconsider the norms of an artist’s CV both generally and within art-historical discourse.

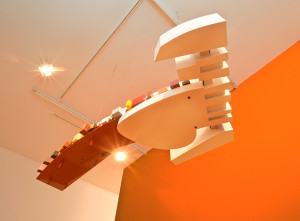

Through the project of this retrospective the work is, last but not least, visible again for art history. Which aesthetic and critical questions do Winteler’s video works evoke in the contemporary Swiss art context? Which aesthetic and critical questions are catalysed by Winteler’s works when seen in combination with powerful works by video and performance artists operating elsewhere in the 1980s, such as Rotraut Pape, Pola Weiss or Esther Ferrer? Which aesthetic and critical questions are stimulated by Winteler’s work within contemporary art historical discourse, in which the dynamic of various forms of historicising this very art, current 30 years ago, can clearly be felt? It is a great pleasure to encounter the video works in physical immediacy in the survey exhibition, to experience the sensory effect and meaning of those works. It is reassuring that this publication finally makes necessarily complex and multifaceted information about this practice publicly available, a practice which, given the time it emerged prior to the digital era, was until recently as good as invisible to internet search engines.(6) This publication enables the appreciation of a biography that is not yet a closed book.

(1) ‘Speelruimte vor beslissingen. En gesprek met Anna Winteler’ in: De Witte Raaf, Nr. 112, Sept.–Okt. 2004, Brussels, pp. 4–5.

(2) In 2019 we have in fact already been in a structurally new and novel phase of art’s parameters for several years. We do not however yet understand it, or when and how it has changed; we equally do not yet have a new, catchy name for it.

(3) Jeff Wall, Depiction, Object, Event, ed. Camiel van Winkel, s’Hertogenbosch 2006 (= Hermes Lecture 2006), p. 27 and p. 21.

(4) In response to this the American artist Lutz Bacher has been exhibiting her work under this name since the 1970s. Natascha Sadr Haghighian, who works from Germany, has, since 2004,

made reference to the website bioswop.net, where CVs can be exchanged and loaned.

(5) The mythical topos of unusual artistic drive is affirmed, for example in articles about the eighty-four-year-old artist Teresa Burga, who, when she was forty, decided to take employment with the customs agency in order to survive economically and to continue her artistic work after office hours. Her recent retrospective and accompanying publication describes this as unbroken activity.

(6) Based on the assumption that parts of, or perhaps the entire, publication will surface, digitised, online. The problematic role of the internet as the first resource for finding information should nonetheless be mentioned. See Mathias Oberli ‘Jeder sein eigener Vasari? Künstlerbiographik und digitale Quellenkritik im Internet’ in: Beate Böckem et al. (ed.), Die Biographie – Mode oder Universalie? Zu Geschichte und Konzept einer Gattung der Kunstgeschichte, Berlin/Boston 2016, pp. 275–284.

Translation into English by Aoife Rosenmeyer

in: Anna Winteler: Ligne Linie Line, Wien, AT, 2019, pp. 133–135.